A town should know its heroes.

Big, small or somewhere in the middle, when a place has noticeably benefited over the longterm from the leadership of its own inspired citizenry, it seems there should be a commonly understood knowledge and community respect for those people.

That’s not so much the case in Hilo when you ask someone under the age of 50 or so about Richard Chinen, whose name occupies a prominent place in the Civic Auditorium he once helped bring into being and then managed.

Curious about the man, you do what everyone does and you go to the internet machine for his Wikipedia page. At the end of the week, there was no Wikipedia page for Chinen. You could find an obituary, an old phone number, but nothing on his background, his rise from Hilo sugar cane fields to one of its most prominent citizens.

He was a driving force behind construction of a new facility after the 1946 tsunami washed out the Hilo Armory, still in use today, but the threat of more flooding caused city leaders to consider a safer location for the future, one with more parking.

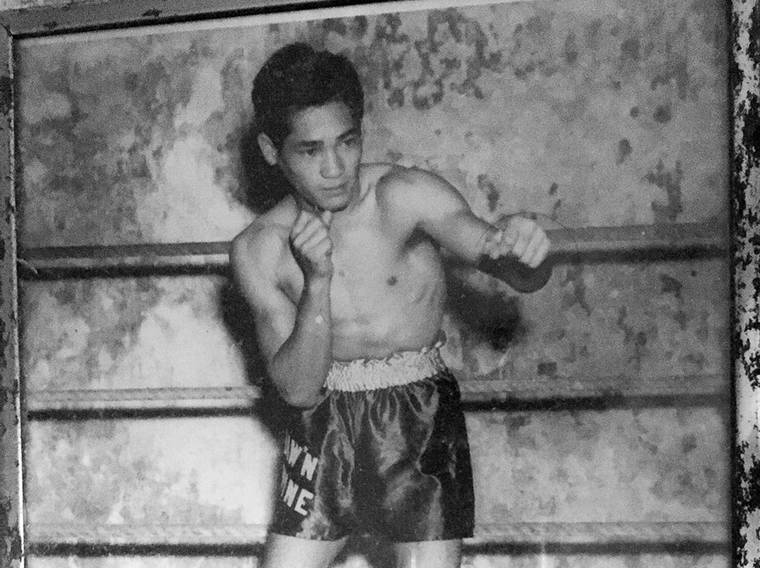

Eventually, city government settled on a spot of land in the Ho’olulu complex and constructed a new Hilo Civic Center. Not long after, they renamed the building Afook-Chinen Civic Auditorium after a well-known coach and Chinen, the one-time boxing champion and war hero.

It was wholly appropriate, but it feels as though an individual like Richard Chinen, ought to have a larger slice of permanence in the minds and hearts of residents than is the case in Hilo with Chinen.

Through contact with the family and some deep dives into research, a fuller understanding of him is available, some of it repurposed for this space.

He grew up dirt poor in a family of Okinawa immigrants, 800 or so feet above sea level, with other immigrants who lived and worked in the Camp 6 sugar cane fields 4 miles above today’s Kinoole Street. The product of their efforts eventually transferred them to headquarters of the Waiakea Sugar Mill, where the Lex Brodie car wash is located today.

Among Hilo’s most significant leaders, Richard Chinen’s name belongs in the first paragraph of any retrospective. He was a guy who found his young life in this town as low to ground as any, his opportunities to advance seemed, at the most optimistic, severely limited.

The family was as poor as all around them, but, as has happened in many mainland locations, those daily hand-to-mouth living conditions generated a particular quest for achievement and, sometimes, liberation from their lives of toil and deprivation.

Developing a level of toughness came as a natural consequence of their bleak existence. They did what they could outside of the home and a lot of them felt a call to the proverbial squared circle, the boxing ring.

It didn’t take long before the largest cluster of boxers from the Hawaii islands were centered on those Okinawa immigrants from the sugar fields in Waiakea Uka. If you’re taking notes, it’s historical fact that Hawaii’s two most prominent basketball players in the post World War II era were Ah Choo Goo and Red Rocha, both from Hilo. Boxing, basketball and Hilo — it all ties together.

Chinen could have never foreseen he would be the leader he later became when he dropped out of Hilo High School before his senior year and moved to Oahu.

He had been trained in the rudiments of boxing by fellow Okinawans Charley Higa and Toy Tamanaha and had his first few bouts here prior to the three of them taking a steamer to Honolulu, where he took a step up in his boxing efforts and saw his horizons expand, both personally and with regard to the community.

The Fort Street CYO became Chinen’s unofficial headquarters as he started winning bouts while also learning a little about baseball and the larger world he was a part of. In little time, relatively speaking, Chinen wasn’t just winning bouts, he was winning a variety of City of Honolulu, Oahu and territorial championships with an eye on the gathering clouds of war.

The same day of the Pearl Harbor attack in December of 1941, members of the University of Hawai’i Reserve Officer Training undergraduates were ordered to campus for the purpose of entering combat. The ROTC was mandatory on campuses of territorial land-grant colleges, and while it was comprised of Japanese American-born citizens — Nisei — their allegiances weren’t questioned despite the fact that they may have looked like the enemy.

Chinen tried to enlist immediately, but he wasn’t in school and people who looked like him weren’t trusted. Chaos was all consuming after the sneak attack on Dec. 7. People were in a panic mode with rumors spreading that Japanese paratroopers had landed in the hills surrounding the UH campus, so the raw, untrained ROTC students were given old rifles to defend the city of Honolulu.

Within six weeks, seeming to be suffering from the fog of war, General Delos Emmons, the military governor under martial law, feeling fears of the community, ordered the Hawaii Territorial Guard be disbanded. The paranoia whispered that those troops were going to turn on the citizenry in the name of Japan.

All of them were volunteers, serving as manual labor support for the U.S. Army’s 34th Engineers at Schofield Barracks. Insulted and discouraged by Emmons, the students petitioned the military governor for a way they could contribute to the war effort.

Eventually, the students formed the Varsity Victory Volunteers, eventually becoming the 442nd Regiment and the 100th Infantry Battalion when sanity returned and racial fears were set aside.

Chinen eventually became among the most decorated soldiers who fought in Italy. Heroic barely touches all he did in the war.

The nation of France awarded him its highest honor, the Croix De Guerre, to go along with the Silver Star, Bronze Star and Purple Heart he was awarded for his efforts.

But when he came home, his lasting impact on Hilo was just starting.

Chinen was elemental in the Big Island Amateur Boxing Club, organizing, managing and training young boxers who knew kids who found ring success by following Chinen’s leadership, much as young baseball players today are encouraged by the efforts of Kolton and Kean Wong, and others who have gone on to major league careers.

When you see it in your neighborhood, with people you know, it suddenly seems more achievable.

And that was true for Kaha Wong, the proud, prolific developer of young baseball talent here that started with his son Kolton and has expanded to an annual transition of Hilo boys to Major League Baseball draftees.

Wong got his start in Hilo playing youth baseball in leagues like Pony and Colt, that were both founded by Chinen.

Fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, it all starts at home, and then in the neighborhoods where keiki see their friends achieve and believe they can do the same.

For that, if for nothing else, we should know the name Richard Chinen, the man who opened doors for Hilo athletics.

Something to remember next time you go into the building that honors him.

Send column suggestions and comments to barttribuneherald@gmail.com